Know what’s a little surreal? Being invited back to your undergraduate alma mater to give the opening professional development workshop to the faculty. I had the pleasure of returning to Westminster College (PA) to facilitate the opening professional development workshop of the AY 2018-2019. We spent the morning talking about designing good group projects, assessing group projects, teaching students to effectively collaborate, and using Scrum in both classes and in professional activities as faculty members.

Know what’s a little surreal? Being invited back to your undergraduate alma mater to give the opening professional development workshop to the faculty. I had the pleasure of returning to Westminster College (PA) to facilitate the opening professional development workshop of the AY 2018-2019. We spent the morning talking about designing good group projects, assessing group projects, teaching students to effectively collaborate, and using Scrum in both classes and in professional activities as faculty members.

I graduated from Westminster in 1998 (yikes, 20 year reunion this year) and loved everything about that experience (except the usual drama associated with being a college-age woman). My experience there is the reason I actively pursued a career at a liberal arts institution rather than a big R1. I consider myself lucky to have been able to attend a small private four-year residential liberal arts college. Not very many people in this country have that privilege, but we were also lucky because most of us came from the working class values inherent in growing up in western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. I could list many transformative experiences reading and writing for different courses, having deep conversations with my faculty mentors, being a sorority leader, editing the yearbook (not very well, looking back). But let’s just say it was an honor to come back to campus and showcase what a Westminster grad can do.

Superfast book review in a nutshell: I love Gamestorming as a great source of classroom,  committee/department, and workshop activities. Most of them just require wall space, sticky notes, and Sharpies as well as a little forethought, and all the activities are designed to be generative – of learning, goals, work, relationships. The book includes games (or activities if you aren’t into gamification) for setting and managing meeting agendas, building common goals and proving accountable to them, team building (in an authentic way, not the cheesy sleep-away camp way), assessing work/team processes, articulating and selecting from options, and many others. I like these types of activities in class because they often get students up and moving, physically drawing out their thoughts instead of typing them. I also always do one, two, or three of these activities in my Agile Faculty workshops on productivity and collaboration.

committee/department, and workshop activities. Most of them just require wall space, sticky notes, and Sharpies as well as a little forethought, and all the activities are designed to be generative – of learning, goals, work, relationships. The book includes games (or activities if you aren’t into gamification) for setting and managing meeting agendas, building common goals and proving accountable to them, team building (in an authentic way, not the cheesy sleep-away camp way), assessing work/team processes, articulating and selecting from options, and many others. I like these types of activities in class because they often get students up and moving, physically drawing out their thoughts instead of typing them. I also always do one, two, or three of these activities in my Agile Faculty workshops on productivity and collaboration.

Pick a game to kick off that committee you are leading, wake up that sleepy 8am class, or just visualize your own goals and intended outcomes for a project, and see what happens!

I’ve really come to enjoy listening to podcasts about higher education, and I was excited to be asked by host Bonni Stachowiack to speak about Agile Faculty and Scrum on her popular Teaching in Higher Ed podcast. Take a listen here!

You can also find me on the Oregon State University eCampus podcast Research in Action, episode 96 talking about the book.

Agile Faculty is also mentioned in Katie Linder’s podcast You’ve Got This (recently rebranded to The Radical Self-Trust Podcast Channel) when Katie talks about using a Scrum board for organization.

I first became aware of Todd Henry‘s work when I was doing a deep dive into design thinking and creativity research a few years ago. His book, The Accidental Creative: How to Be Brilliant at a Moment’s Notice, is kind of a guide book for creative professionals who make their living on their ideas. The book maps a process that he’s created and honed over years as a creative, trainer, consultant, author, and speaker (see a full services and creative resources on the Accidental Creative agency website). Henry provides strategies to help readers figure out how to focus energy and attention on the most important, value-creating work while cultivating inspiring relationships and creative inputs and managing time effectively.

thinking and creativity research a few years ago. His book, The Accidental Creative: How to Be Brilliant at a Moment’s Notice, is kind of a guide book for creative professionals who make their living on their ideas. The book maps a process that he’s created and honed over years as a creative, trainer, consultant, author, and speaker (see a full services and creative resources on the Accidental Creative agency website). Henry provides strategies to help readers figure out how to focus energy and attention on the most important, value-creating work while cultivating inspiring relationships and creative inputs and managing time effectively.

His catchphrase for this book, and his long-running Accidental Creative podcast, stuck with me for a long time: “Cover bands don’t change the world.” As a faculty member, I am driven to change the world in some way, and the best way to do that is to do the things only I can do. As I’ve read more of his work and listened to hours of podcast episodes while working out, the more I see how many of the situations, challenges, and inspirations that drive creative professionals are at work in academia as well. Academics are creative professionals, no doubt about it. We have a good deal of control over our schedules, what we teach and research, how we teach and research. We are driven to make an impact on our students, peers, disciplines, and communities, to engage in important

read more of his work and listened to hours of podcast episodes while working out, the more I see how many of the situations, challenges, and inspirations that drive creative professionals are at work in academia as well. Academics are creative professionals, no doubt about it. We have a good deal of control over our schedules, what we teach and research, how we teach and research. We are driven to make an impact on our students, peers, disciplines, and communities, to engage in important  conversations, to add value to the world. And we can also work ourselves into a hole of overwhelm or, worse, burnout. We have to manage our creative energies even within the steady rhythm of semester after semester. Like I do in Agile Faculty, Henry lays out strategies to manage your creative energy, acknowledging that creative professionals (like faculty) do need a process to harness and sustain that energy.

conversations, to add value to the world. And we can also work ourselves into a hole of overwhelm or, worse, burnout. We have to manage our creative energies even within the steady rhythm of semester after semester. Like I do in Agile Faculty, Henry lays out strategies to manage your creative energy, acknowledging that creative professionals (like faculty) do need a process to harness and sustain that energy.

This summer, I picked up Henry’s second book (there are four total as of 2018), Die Empty: Unleash Your Best Work Every Day, because of its main themes of focusing on creating  value with your work every day and avoiding stagnation and expectation escalation, topics important to me as I work through an episode of burnout. Henry defines work as anything you do that adds value to the world with the tools and resources you have. This is a concept I’ve been thinking about for most of the summer after reading it – I’m always working and even find ways to turn fun into work (I ride a horse? I must compete! Yeah, no). But what value am I creating? How much of what I’m doing is am I doing just because I always have, or because I feel I have to top my previous achievement, or because I feel like I should do it, regardless of if that is really true? How can riding my horse not be “work work” but instead something that simply adds value to my life?

value with your work every day and avoiding stagnation and expectation escalation, topics important to me as I work through an episode of burnout. Henry defines work as anything you do that adds value to the world with the tools and resources you have. This is a concept I’ve been thinking about for most of the summer after reading it – I’m always working and even find ways to turn fun into work (I ride a horse? I must compete! Yeah, no). But what value am I creating? How much of what I’m doing is am I doing just because I always have, or because I feel I have to top my previous achievement, or because I feel like I should do it, regardless of if that is really true? How can riding my horse not be “work work” but instead something that simply adds value to my life?

In talking about work as value, Henry articulates several deeply held myths that we we believe about work and that hold us back from our best work. The two I’m processing most this summer are

MYTH: “Recognition for work is the highest form of currency.”

MYTH: “You are worth only what you create.”

I’m just going to let those sit there for us all to think about. Can you see yourself or a colleague int these myths? Does academia perpetuate these myths to our great detriment? (I’m going to say yes on that one, sorry not sorry.) What value do es our work create outside of these myths, and how can we support each other, our grad students, and our undergraduates?

If you appreciate the style of work by Seth Godin, Adam Grant, Dan Pink, Dori Clark, and that crew, you’ll enjoy Henry’s books. Some academics might dismiss Henry’s work because his insights and recommendations are built on his business and personal experience rather than empirical research, but I like to mix books like these into my reading because I love seeing how we can think about ourselves and our work from different angles and learn new approaches (hence, Agile Faculty, right?). These are easy reads that I recommend if you need a little injection of creativity to think of yourself as the creative pro that you are.

“Redesigning higher education demands institutional restructuring, a revolution in every  classroom, curriculum, and assessment system. It means refocusing away from the passive student to the whole person learning new ways of thinking through problems with no easy solution. It shifts the goals of college from fulfilling course and graduation requirements to learning for success in the world after college. It means testing learning in serious and thoughtful ways, so that students take charge of what and how they know, how they collaborate, how they respond to feedback, and how they grow. It teaches them how to understand and lead productively in the changing world in which they live.” (8-9)

classroom, curriculum, and assessment system. It means refocusing away from the passive student to the whole person learning new ways of thinking through problems with no easy solution. It shifts the goals of college from fulfilling course and graduation requirements to learning for success in the world after college. It means testing learning in serious and thoughtful ways, so that students take charge of what and how they know, how they collaborate, how they respond to feedback, and how they grow. It teaches them how to understand and lead productively in the changing world in which they live.” (8-9)

If you read my previous post about responding to change over maintaining the status quo in higher education, you can pretty easily imagine how I feel about Davidson’s 2017 book, The New Education: How to Revolutionize the University to Prepare Students for a World in Flux. My underlines are plentiful, and my annotations peppered with “hell yes!”, “finally,” “it’s about time.” While many likely know Davidson from her work with HASTAC, which has moved from a site for scholars to discuss how to integrate technology into learning into a full-blown hub for innovation in higher ed. This new book is a direct outgrowth of that evolution. Davidson wants us to actually rethink education as a whole, not just tiny pieces within our immediate control in one context:

“The new education isn’t simply a change in curriculum or implementation of a new kind of pedagogy. It’s not just a course or a program. It’s all of the above, undergirded by a new epistemology, a theory of knowledge that is deep, synthetic, active, and meaningful, with real impact in the world. In the end, the new education is also a verb, one that empowers our students with better ways to live and thrive in a complicated world.” (161)

Davidson leaves no stone unturned in her well-documented assessment of higher education. The first chapter reviews the history of American higher education to explain – and de-naturalize – many of our trenchant systems in the academy. Other chapters cover the crucial role community colleges can and should play in the higher ed landscape, the role of technology in the future of education and what educational practices should remain offline (MOOCs can’t solve everything), and ways higher ed should prepare students (regardless of major or status) to make an impact on the world. She also doesn’t shy away from issues of cost and assessment, the rank-and-sort function inherent in the current system. In the end, she calls on us all to collaborate in this new vision:

“We need educators and administrators themselves committed to redesigning an ethical, democratic, pragmatic, forward-looking education, one that not only uses technology wisely and creatively but also understands its limits and its impacts and addresses its failing. We need individuals and institutions to work together to rejuvenate an antiquated system for our accelerating times and to ensure that the solutions we craft address the real problems rather than just generating new ones…[our] students are all asking for the same thing: a new education designed to prepare them to lead a meaningful like in the years after college.” (248, 254)

And each and every one of our students deserves that. Highly recommended!

This post is part of a series looking at the Agile Faculty Manifesto. Read the Manifesto in this series preview post or in Chapter 1 of the book. This post explore what it means to focus on responding to change in higher education.

Agile Faculty respond to changing environments rather than maintain status quo of academia.

<My academic brain is telling me I should support the following post with extensive research about the history of the university, but I’m just going to go with my gut here. I do recommend Cathy Davidson’s recent book, The New Education, as a great resource.>

In the afterword to Agile Faculty, I spend time in a thought experiment, imagining what Agile higher education might look like, imagining what might happen if we broke the legacy features of university structures and tried something radically different, something more flexible and Agile/agile, something truly responsive to the students and communities we serve. And much of it is a pipe dream.

The academy is a paradox – we are supposed to educate future citizens so they are ready to  contribute economically, socially, and civically…but we do it through a mishmash of anachronistic systems – the medieval university ideal (see regalia, which is the bane of my existence during mid-May outdoor graduations in North Carolina), the German research university model, Harvard’s elective system developed by Charles Eliot in the late 1800s, the Carnegie system for counting hours and seat time, etc. Responding to change in academia then can be a paradox as well, when our reproduced and entrenched systems are often at the heart of the problem.

contribute economically, socially, and civically…but we do it through a mishmash of anachronistic systems – the medieval university ideal (see regalia, which is the bane of my existence during mid-May outdoor graduations in North Carolina), the German research university model, Harvard’s elective system developed by Charles Eliot in the late 1800s, the Carnegie system for counting hours and seat time, etc. Responding to change in academia then can be a paradox as well, when our reproduced and entrenched systems are often at the heart of the problem.

In my five years teaching as a graduate student and 11 years as a faculty member, I have gone through periods when I have fiercely defended my “turf” from perceived threats, justified the existence of programs and courses in my area, argued with people creating courses just to teach their esoteric research specialty, spent large chunks of time fearing being scooped before my research and book came out, and complained about teaching (and about other people complaining about teaching) service courses. I have attended meeting after meeting that could have been accomplished by email and a good Google Doc. I’ve participated on committees and work groups to design university programs and enhance curricular offerings, even as we struggle between what we perceive to be the demands of academic rigor and job-readiness, a struggle felt most deeply in the humanities.

It wasn’t until after my (positive) tenure decision that I really started to interrogate these structures and create new options, even from within the system itself (see my work on the Design Thinking Studio in Social Innovation). But really I have supported and reproduced the systems of higher education through my teaching, research, and service activities. Because old habits are almost impossible to break when they are so entrenched in our academic psyches. I read a Twitter thread recently about power and hierarchy in academia, arguing that the entire underlying currency for academics is respect and reputation, gaining it, bestowing it, withholding it. The original impetus for this particular thread was issues of sexual harassment in the academy, but it resonates on so many levels. We can’t fix problems with the tools we used to create them.

It wasn’t until after my (positive) tenure decision that I really started to interrogate these structures and create new options, even from within the system itself.

The world around us is changing (obviously, it always has been), and it can often feel like we (at least I) are stuck in a system that doesn’t make sense. Why is a narrowly focused single-authored manuscript that will appeal to a tiny readership the gold standard for many tenure decisions? Or only publications in certain “high quality” journals count rarely journals about pedagogy or faculty development (which surely are just side interests, right)? What does tenure even mean anymore, especially in the face of overworked, undervalued adjunct labor teaching classes other academics are trying to get out of teaching? Why do we still have semesters and seat time requirements? Do people really learn from sitting in a chair in a classroom for 200 minutes a week for 14 weeks? Why do we still grade papers on an A-F scale when we know we have trained students to work for a grade instead of for learning, when we know that will be a damaging perspective to take into the work world?

I could go on. I’m sure you agree with some of these points and disagree with others, perhaps strongly. I’m sure I would feel the same about your points. But, really, my point here is that if we truly want to prepare students for the opportunities, challenges, and hard struggles they will face as citizens, we need to rethink our systems for helping their skill and knowledge development. If we want to relate more to the public and legislators angry as they imagine faculty sitting in comfy chairs reading 24-7, we need to be more public with what we do, why we do it, and how it contributes to society. etc. etc.

Because of the faculty governance model, it falls to us to recognize the changes in our world and students and be actively responsive rather than reactionary and protectionist. Yes, we can still demand rigor and critical thinking and excellent writing and speaking skills while re-imagining what higher education could look like, the experiences, the rhythms, the relationships, the learning, the acting. What would your response to change be, and how will you act on it?

The subtitle of Story Driven tells you pretty much exactly what you need to know about the content: You don’t need to compete when you know who you are. Targeted and professionals and entrepreneurs, Story Driven is about stopping to articulate goals, purpose, intention, and actions that are foundational to your business. Jiwa argues persuasively that when you can clearly understand who you (and your business) are, that becomes your competitive advantage and the story you need to tell to attract customers, clients, followers.

The subtitle of Story Driven tells you pretty much exactly what you need to know about the content: You don’t need to compete when you know who you are. Targeted and professionals and entrepreneurs, Story Driven is about stopping to articulate goals, purpose, intention, and actions that are foundational to your business. Jiwa argues persuasively that when you can clearly understand who you (and your business) are, that becomes your competitive advantage and the story you need to tell to attract customers, clients, followers.

This book reminds me of Simon Sinek’s Start with Why because she asks you to really focus on who you are, what you value and stand for, why you want to do something, and how you can use that to develop a powerful sense of your identity, as a person and entrepreneur. Story Driven is divided into two main sections – her discussion of narrative identity and how to craft it followed by a number of case studies of stories organizations tell. What I like about this section is that it includes a wide variety of examples from across areas; whereas, Sinek tends to get stuck in Google and Apple worship.

Jiwa provides a structure for framing a story that includes reviewing your backstory or journey to now; articulating values, purpose, and vision; and then developing the strategy, which she defines as “the alignment of opportunities, plans, and behavior: how you will deliver on your purpose and work toward your aspiration, while staying true to your value” (43). As a mid-career faculty member experiencing some burnout, I like this framework for some deep personal reflection about my path to now and into the future. On pages 134-142, Jiwa provides very useful prompts to give structure to this reflection.

Jiwa’s focus on articulating identity and aligning goals, self, and actions to tell a coherent story make a lot of sense in terms of faculty life, especially when we come to personal crossroads such as mid-career malaise, the end of a research agenda, or a time of burnout. My returning to what attracted us to academia in the first place and mapping our stories, we can better see where we’ve been, how we have been enacting our values (or not), and how we might continue with clearer purpose. She asks, “What’s at the heart of your story? What’s the reason you got out of bed this morning?…It’s the deep, often unspoken, desire to change something you care about changing and the belief that it’s possible. [But] sometimes we forget why we started…” (32).

I enjoyed this book and this way of thinking about my professional experience as a story-driven narrative that I can control when I know where I’ve been, what I value, and what I aspire to. Agile Faculty may find this a useful exercise that can be done in parallel with writing user stories and before creating a backlog. It never hurts to be reflective before acting, not just after.

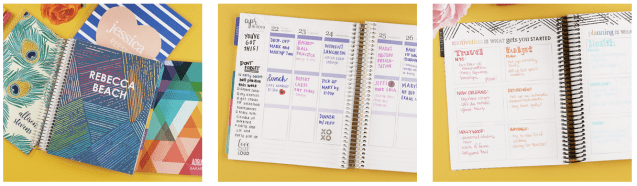

I love paper planners. While my software developer husband keeps trying to shove his Google Calendar at me, I remain loyal to print. I’ve used the Erin Condren LifePlanner for years, but this academic year, I wanted something different. I didn’t just want a place to put my schedule; I wanted a place to also chart goals and develop morning and evening routines to help alleviate some of the burnout I’ve been feeling. I looked at a range of paper planners, so I thought I’d share with you what I see as the pros and cons of best and which planner I ultimately landed on for 2018-2019. I’m sure you are waiting on pins and needles to know.

I love paper planners. While my software developer husband keeps trying to shove his Google Calendar at me, I remain loyal to print. I’ve used the Erin Condren LifePlanner for years, but this academic year, I wanted something different. I didn’t just want a place to put my schedule; I wanted a place to also chart goals and develop morning and evening routines to help alleviate some of the burnout I’ve been feeling. I looked at a range of paper planners, so I thought I’d share with you what I see as the pros and cons of best and which planner I ultimately landed on for 2018-2019. I’m sure you are waiting on pins and needles to know.

But, first, a word about the benefits of a paper planner. There are lots of reasons I prefer paper. First is, well, paper. I’m a print person. I have my students print out their papers for grading; I realized I ended up spending way too much time per paper when I graded electronically. I print research articles to read and annotate and edit my own writing on paper. I did try using my Outlook Calendar when I had my precious Blackberry Bold, but it felt so impersonal and open to anyone else at the university who had Outlook (I’m sure there were probably ways to fix that, but oh well). The act of physically writing a meeting or a deadline in the paper planner fixes it more in my mind than with an electronic calendar. I also like being able to personalize with different color codes, doodles, and stickers.

So which planners did I review in July?

Erin Condren LifePlanner

When I first found this planner, I liked the personalized covers, the colorful monthly and weekly sections, and the three boxes per day to add your schedule. It includes monthly spreads, event stickers, perpetual calendars, inspirational quotes, and more recently, boxes up front for adding goals. They started as a little woman-owned business in southern California and have grown exponentially in the last few years; you can even find planners and accessories at Staples now. They’ve added more ways to personalize with a wide variety of now interchangeable covers, different colored coils, colorful and neutral palettes, and three different layouts for the week – the original three box view, hourly, and horizontal. With these changes, they have made the planner a little more man-friendly too, as the planner really is targeted at women, used frequently by lifestyle, food, and mommy bloggers especially.

Over time, I found myself spending too much effort matching my pens to the monthly color schemes, decorating each week in a specific palette of pens and washi stickers. I hadn’t found a good way to use this planner to track projects and goals either. So, great for folks who like lots of colorful and artsy options in a planner but not as awesome for tracking work.

Over time, I found myself spending too much effort matching my pens to the monthly color schemes, decorating each week in a specific palette of pens and washi stickers. I hadn’t found a good way to use this planner to track projects and goals either. So, great for folks who like lots of colorful and artsy options in a planner but not as awesome for tracking work.

Passion Planner

The Passion Planner is designed to help you articulate goals, draw your Passion Roadmap, and track projects throughout the days and weeks of the month. It provides regular space to plan and reflect on your time. Passion Planner includes timed weekly spreads (below) and monthly calendars, all undated so you can start using the planner at any time during the year. Each weekly spread includes space for articulating weekly and daily intentions, motivational quotes, space for personal and professional to-do lists, a spot for gratitude, and a space for a small piece of your Passion Roadmap or doodles. It’s about as thick as the EC LifePlanner and soft rather than coil bound. I ordered this planner and liked it, but as I thought about setting it up for Fall, I realized it was a little too structured for me, so I returned it.

Full Focus Planner by Michael Hyatt

The Full Focus Planner comes from time management guru Michael Hyatt and incorporates all his tips and processes in one undated, hardbound book. This one is more business-like and includes great features like pages to articulate your daily routines, goal trackers, and weekly and month reviews. Each day gets a full two-page spread that includes space for your “Daily Big 3” goals, a task list, daily appointments, and a full page for notes (see below). I thought long and hard about this one as it seemed to have everything I wanted in terms of tracking daily rituals, projects, goals, and my days. But the big con for me was that, because each day gets its own two-page spread, this planner only lasts three months; it would be huge if it covered a full year. So you have to buy four of them to get through the year, while more than doubles the cost of an EC or Passion Planner. And I couldn’t figure out how I could record future meetings and events without carrying multiple books around. So this one was a no for me.

Panda Planner

Panda Planner

I know you’ve been in suspense, but I chose the Panda Planner Pro for this academic year. The Panda Planner comes in two different sizes, and both sizes include ways to think about you month, week, and day. They have space for breaking down projects and priorities, keeping a focus and daily habit in mind, and planning and reviewing months, weeks, and days. I chose the larger Pro planner with comes with 12 undated monthly spreads, about six months’ worth of weekly planning pages, and six months’ worth of daily pages (see below). The only thing I don’t like is that it only includes weekly review pages rather than weekly spreads so I can’t see my schedule for the week in one place. I’m going to use the monthly spread for that and see how it goes. The planner is large enough that I should have room to add everything. I’ll use it until it runs out in January and then decide it I want to get another or try something new.

I know you’ve been in suspense, but I chose the Panda Planner Pro for this academic year. The Panda Planner comes in two different sizes, and both sizes include ways to think about you month, week, and day. They have space for breaking down projects and priorities, keeping a focus and daily habit in mind, and planning and reviewing months, weeks, and days. I chose the larger Pro planner with comes with 12 undated monthly spreads, about six months’ worth of weekly planning pages, and six months’ worth of daily pages (see below). The only thing I don’t like is that it only includes weekly review pages rather than weekly spreads so I can’t see my schedule for the week in one place. I’m going to use the monthly spread for that and see how it goes. The planner is large enough that I should have room to add everything. I’ll use it until it runs out in January and then decide it I want to get another or try something new.

So that’s my quick tour through paper planner land. What type of schedule-minder do you prefer, and why?

I’m late to podcasts, thinking for a long time that they were just recordings of NPR radio shows, series like Serial, or Wayne’s World-style pet projects. Yes, pretty uninformed perspective. I really started listening podcasts about two years ago. Trying to find a way to stop fighting with my husband over who controls the radio on our regular eight-hour drives to visit my family in Pittsburgh, podcasts became our savior. We agreed on shows about space, political theory, and cultural topics.

Then I discovered all the interesting higher education and creative professional podcasts, and I was hooked. I even started regularly exercising so I could find dedicated time to work my way through different shows’ backlogs of episodes (hey, whatever works, right?). Below is a quick list of my favorites and the Twitter handles of the hosts.

Higher Education in General

Teaching in Higher Ed – hosted by Dr. Bonni Stachowiak. Great interviews with academics of all stripes focused on teaching specifically with some tips on academic life. I’ll be on in August 2018!

Research in Action – production of Oregon State University Ecampus, hosted by Dr. Katie Linder. Katie pops up a lot in the list, but it’s well deserved. She’s one of the most prolific higher ed podcasters out there. This particular show is interview-based and covers all aspects of academic life and careers. I was on recently – here’s the link to my episode.

You’ve Got This – hosted by Dr. Katie Linder. This one is about “surviving and thriving in an academic life” and covers a variety of topics like setting and managing research agendas, productivity strategies, pitching and writing books, and a hundred other ways to navigate faculty work.

Future U – hosted by Jeff Selingo and Michael Horn. This podcast is hosted by Chronicle contributor Jeff Selingo and higher ed researcher and consultant Michael Horn. Each episode includes an interview with a higher ed or ed tech leader as well as time for the hosts to discuss what they learned from the conversation. Covers many topics surrounding the business and future of higher education in the US.

Higher Ed Now – production of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni. This podcast looks at higher education through the lens of policy and hot topics in the industry with great interviews and conversations.

Academics with Side Gigs

AcademiGig – hosted by Dr. Katie Linder and Dr. Sara Langworthy. Katie’s back (and I even left two other podcasts off of this list), and this time she is joined by Sarah Langworthy to talk about academics running their own businesses. Katie is employed by a University but has a robust side business, speaking, writing books, and designing websites for academics. Sara, a child psychologist, left academia to start two side business which are her primary income streams now. The show is about the joys and challenges of starting your own side gig, chock full of lots of advice, real stories, reality doses, and encouragement.

Academics Mean Business – hosted by Dr. Lindsay Padilla. Lindsay is a former academic now running a consulting business helping entrepreneurs design online courses. On this podcasts, she interviews creative academic entrepreneurs about life after the academy.

Other Favorites

Accidental Creative – hosted by Todd Henry. I’m kind of obsessed with Todd Henry’s work this summer, books and podcasts. While his advice isn’t empirically based, he has a great deal of experience supporting creative, and the more I listen/read, the more connections I see to faculty life because faculty are, in many ways, self-managed creative entrepreneurs.

The Savvy Psychologist – hosted by Dr. Ellen Hendriksen. Helpful, easily digestible episodes cover a variety of psychology topics such as getting over disappointment, reasons for procrastinating, and damaging myths we buy into. I appreciate that each episode is grounded in research and offers helpful tips you can use.

WorkLife – a TED production hosted by Dr. Adam Grant.Adam Grant is everywhere these days. Great podcast about common workplace issues, most of which can translate to the academy as a workplace. One interesting feature is the commercials – rather than just speed read a pre-written ad, Adam interviews people at the sponsors company and tells stories about their innovations.

This is the final post from a series I wrote in 2012 about writing and publishing with undergraduate students. I’ll be publishing this series every other Thursday over the summer. For more recent research and resources, visit the new International Journal for Students as Partners and a special issue of Teaching and Learning Inquiry that I co-edited on students as co-inquirers.

OK, so you’ve asked students to work with you, figured out a SoTL question to address together, and collected your data. Now how exactly do you do the actual writing?

Dissemination is an important part of SoTL work as we continue to build the knowledge base surrounding teaching and learning outside of more traditional educational research. For many of us, writing can be a challenge – whether it’s motivating yourself to write during a busy week in the semester, avoiding distractions, deciding what to write when you do have some time, or just fighting writer’s block or procrastination. Accountability is always an issue given our competing responsibilities, even when you have some awesome motivation like AcWriMo.

Dissemination is an important part of SoTL work as we continue to build the knowledge base surrounding teaching and learning outside of more traditional educational research. For many of us, writing can be a challenge – whether it’s motivating yourself to write during a busy week in the semester, avoiding distractions, deciding what to write when you do have some time, or just fighting writer’s block or procrastination. Accountability is always an issue given our competing responsibilities, even when you have some awesome motivation like AcWriMo.

Given that I teach and study writing, I certainly don’t find it onerous, but it definitely take me a while to warm up before I get into a grove on a new piece. Bringing students into your very personal writing process requires some finesse and a good attitude! Here are some tips that can be helpful during the writing process:

1. Be honest with students about your usual writing process. Students often are mystified that, even for faculty members, writing is developmental and ongoing learning process. I like to talk my students through the publication process but also my own process so they understand that we can be on a relatively level playing field when we collaborate. My own process is more cerebral; I’m what Lisa Ede calls a “heavy planner,” so I need to do all my reading, thinking, planning, and even some mental drafting before I ever put fingers to keyboard. That can be frustrating if you are working with “heavy revisers” or might look like procrastination to others (it’s really not for me, my mother had the same process when she went back to college – it’s genetic). So before we write we have an open discussion about our writing processes so we understand each other as fellow writers.

2. Decide how everyone’s voice will be represented in the article. Will you write from a unified collective voice? Will you each have a personal voice in the piece? Will you refer to each other in the first or third person? If you are writing for a disciplinary publication, some of those conventions will be decided for you. But many SoTL publications are much more open in the structure of articles and how authors articulate themselves. I’ve found that, for me, it’s just easier if everyone has their own voice – we write the intro and conclusion collectively, then have our own sections from our first person perspectives, usually a related introductory narrative that illustrates a research point and then a section that pulls the addition data in to further the argument. This allows the best of both worlds – and it spreads the writing work around so that your student co-authors don’t become intimidated thinking about writing 30 pages or 8000 words.

3. Create the outline, and decide who is responsible for what. I’ll often take the first stab at an outline then ask the students to review and flesh it out before our next meeting. I’m the experienced writer here, so it would be unfair to throw them into the deep end at this point. We work on the outline together, even sorting different bits of the data and findings into the piece. We then decide who wants to write what section. This has been relatively easy so far. Most of my co-authors either had a specific opinion or were happy to write any section, so it all balanced out. In these cases, I have usually taken on the literature review and a first draft of the introduction (using the thesis we collectively developed), then asked the students to take the lead on the conclusion.

Because I’m coauthoring SoTL pieces rather than strict disciplinary research, and because my students are unlikely to be going on to graduate school in the field, I’m not worried about having them work through the literature. We certainly read a few articles and other lit reviews so they get a sense of what that looks like, but I write it…frankly because in this case it’s just faster. Now if you were doing disciplinary scholarship, socializing students into that skill might be far more important, so you can decide what’s best for your students in those cases.

4. Develop a realistic writing timeline together with specific, achievable goals for everyone. When my head is totally in the game and my heavy planning is complete, I can sit down and bang out a well-formed 25-page draft in two or three days (if my schedule is clear). For heavy revisers and most students, that’s ludicrous (it is for me too sometimes). Earlier in the writing process with your student co-authors, you probably did some freewriting, and that’s a good place to start your schedule-thinking. Talk about how long that took, how comfortable they are with the writing style, and what their schedules look like over the next few weeks. I try to be ambitious without being crazy about it. Typically I set a 5-6 week writing period, and we discuss what we will have to or for each other by specific set weekly dates. The schedule will definitely need to be adjusted, but it gives the writing activities structure and the writers accountability. The weekly deadlines are good for me too because I don’t want to not hit a deadline when I’m trying to model professionalism and prioritization. We usually would meet a day or two after one of those deadlines to exchange revising advice and feedback, then move forward toward the next goal.

5. Build in a lot of revision time. And resist your inner old blue-haired grammar teacher. Arguably revision is the most important and most challenging part of this writing process because revision can be mysterious for students. While we might teach excellent strategies for revising academic writing, we know that it’s often more expedient for them to skip it and just turn something in. But revising your article is the time to be at your best as a mentor and to control your own urges to “just fix it” so that students really see you as a co-author. I certainly struggle with this a great deal, usually because I know what the student is trying to say and it’s just easier to change it myself…and because I’m an excellent style mimic and I know I’ll get away with it (I worked on a mentor’s textbook in graduate school, and to this day she isn’t sure whether she wrote those chapters or I did).

So I try to check my natural tendencies until it’s useful for the students to be learning, and as we get closer to the end I let my editor out slowly. I’ve found that students really appreciate this because it shows I take their writing seriously, that I want them to help me improve mine as well, and that I’ll make sure everything is up to publication standard in the end. And PS – going overboard fixing every single grammar mistake after the first draft is really a waste of time since much of that work is likely to get revised anyway. Revise for content before editing for grammar.

Hopefully these tips will help you manage the collaborative writing process with your student co-authors and result in many excellent experiences and publications. Thank you for reading this series, and I hope you have found it helpful. Looking forward to seeing your co-authored publications in SoTL journals very soon!